Across the valleys and ridges of Bosnia, medieval tombstones still rise from the earth. These stećci, carved with crosses, spirals, and scenes of hunters on horseback, mark more than graves. They are symbols of a vanished faith, one that stood apart from its neighbors and came to be known as the Bosnian Church. For centuries this church has been described in contradictory terms. To its enemies it was heretical. To later admirers it was a proud declaration of independence. To modern historians it remains one of the most intriguing and misunderstood Christian traditions of the Middle Ages.

A Church Without a Master

The Bosnian Church emerged in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries in a land where neither Catholic nor Orthodox authority held complete sway. Bosnia’s mountains and valleys, difficult to reach and difficult to govern, created conditions for a religious life that was independent of distant bishops.

Its adherents called themselves krstjani, or simply “Christians.” Their leaders were known as “good Bosnians,” a term that captured both their role in society and their spiritual authority. The structure was simple. At its head stood a figure called the djed, or grandfather, supported by a council of elders. Below them were the gosti, or “guests,” wandering clerics who visited communities scattered across the land. Monastic houses, known as hiže, provided centers of worship and study.

The Bosnian Church was less formal and less hierarchical than its neighbors. Clergy lived modestly and often acted as mediators between rival nobles. Their closeness to everyday life gave the Church a different character from the great episcopal structures of Rome or Constantinople.

What Did They Believe?

Much of what the Bosnian Church believed has to be pieced together from fragments. Written records are sparse and nearly all contemporary descriptions were penned by outsiders, usually hostile ones. Even so, a picture begins to emerge.

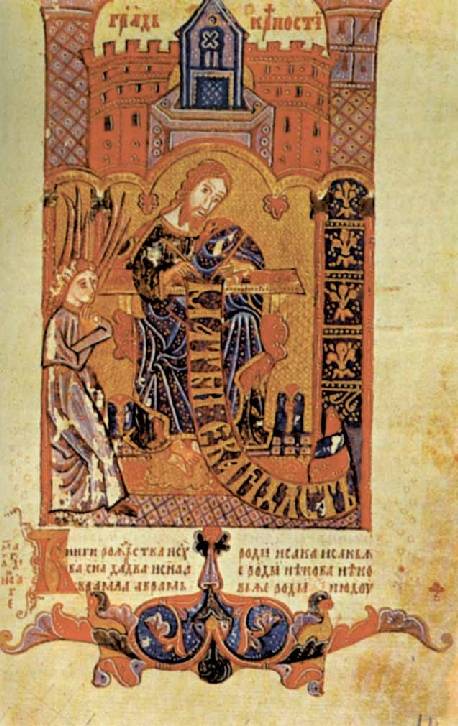

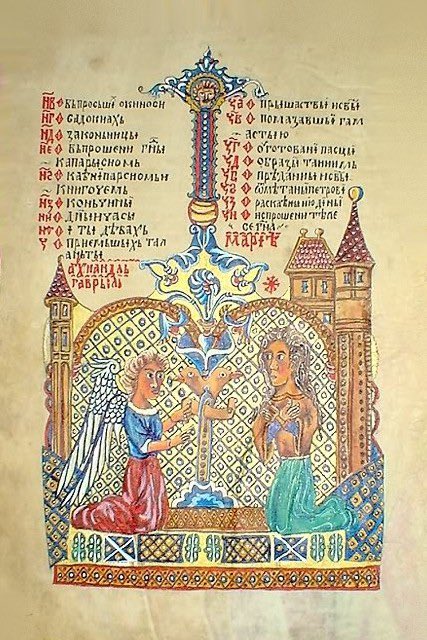

Krstjani professed belief in one almighty God, understood as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. They revered Christ as the incarnate Son of God and recognized Mary, the apostles, and the saints. They read both the Old and New Testaments and accepted the authority of Christian scripture.

Sacraments formed part of their practice, although perhaps in simpler or more flexible form than elsewhere. Confession and penance were observed. Fasting was expected. Communion was taken several times each year. Clergy were required to keep the hours of prayer and to maintain scriptural study. The cross was used as a sacred symbol, despite repeated claims from critics that the Bosnian Church rejected it.

The evidence suggests not a radical heresy but a Christianity that adapted itself to local needs and conditions. The Bosnian Church did not seek to overturn Christian doctrine. Rather, it resisted domination by distant powers and maintained an identity rooted in Bosnian life.

Why Were They Called Heretics?

The label of heresy was as much political as it was theological. Bosnia lay on contested ground, desired by Hungary and watched closely by Rome. To describe its church as heretical provided justification for intervention. Campaigns were launched against Bosnia in the thirteenth century under the banner of crusade, although they achieved little.

To foreign rulers, the Bosnian Church was dangerous not because it denied Christ but because it refused subordination. Its priests answered to no bishop in Rome or Constantinople. Its people identified themselves as Bosnians rather than as subjects of outside ecclesiastical centers. The charge of heresy became a convenient weapon in struggles for power.

A Church in Decline

The Bosnian Church endured into the fifteenth century, even as pressure mounted from both Catholic and Orthodox neighbors. Kings such as Tvrtko I recognized and believed in its importance, allowing it to coexist alongside foreign envoys while carefully balancing alliances.

The arrival of the Ottoman Empire changed the landscape. After the conquest of Bosnia in 1463, the Church gradually faded. Some of its followers converted to Islam, others joined Catholic or Orthodox communities. By the end of the century the Bosnian Church no longer existed as an institution, though its memory lived on.

Legacy and Memory

For centuries the Bosnian Church has been remembered through the writings of its opponents, who portrayed it as a dangerous sect. Yet the evidence that survives points in another direction. It was not a faith defined by dualism or rejection of Christian truth, but by independence, simplicity, and closeness to its people.

The stećci that scatter the Bosnian landscape today are reminders of that world. They are silent, but they speak of a community that sought to live its faith in its own way, neither wholly Latin nor wholly Byzantine, but distinctly Bosnian.

The story of the Bosnian Church is a lesson in how history is shaped. Labels of heresy or orthodoxy tell us as much about politics and power as they do about belief. In Bosnia, those labels obscured a deeper truth: that its people nurtured a Christian tradition that belonged first to themselves, and in doing so preserved a sense of identity that would endure long after the institution itself had vanished.