The medieval history of Bosnia spans from 1180 to 1463, a period marked by territorial expansion, economic prosperity, political maneuvering, and religious complexity. Despite being overshadowed by neighboring powers like Hungary and Serbia, Bosnia developed a unique identity and, under the Kotromanic dynasty, rose to prominence as a kingdom in the Balkans. This article explores the key rulers, territorial changes, religious dynamics, and eventual fall of medieval Bosnia.

Early Bosnia and the Reign of Ban Kulin (1180–1204)

Ban Kulin is widely regarded as the founder of medieval Bosnia’s political and economic stability. His reign saw Bosnia transition from a loosely controlled frontier region of Hungary into an autonomous entity. Kulin’s greatest achievement was the Charter of Ban Kulin (1189), a trade agreement with the Republic of Ragusa (modern-day Dubrovnik), which provided Bosnian merchants with commercial privileges and encouraged economic growth.

While Kulin was an effective leader, his rule was not without controversy. The Bosnian Church, a Christian sect that existed independently from both the Catholic and Orthodox churches, was a source of concern for Rome. Accusations of heresy led to pressure from the Pope and Hungary, forcing Kulin to convene the Council of Bilino Polje in 1203, where he reaffirmed Catholic allegiance. Despite this, the Bosnian Church persisted and remained a distinctive religious institution in the region.

Expansion Under Ban Stephen II Kotromanic (1322–1353)

By the early 14th century, Bosnia had grown into a formidable regional power under Ban Stephen II Kotromanic. His strategic diplomacy and military campaigns expanded Bosnia’s borders significantly. He successfully incorporated Zahumlje (Herzegovina), parts of Dalmatia, and Usora and Soli (modern northern Bosnia), strengthening Bosnia’s control over trade routes and resources.

Stephen II navigated complex relationships with powerful neighbors, particularly Hungary and Serbia. Though Bosnia was nominally a Hungarian vassal, it exercised considerable autonomy. One of his most significant moves was securing alliances through marriage diplomacy, ensuring that Bosnia remained politically stable.

Religiously, the presence of the Bosnian Church remained a contentious issue, as both Catholic and Orthodox leaders sought to bring Bosnia under their influence. However, Kotromanic largely tolerated religious plurality, which helped maintain internal peace but also contributed to Bosnia’s long-term vulnerability.

King Tvrtko I Kotromanic (1353–1391): The Golden Age of Bosnia

The pinnacle of medieval Bosnia’s power came under King Tvrtko I Kotromanic. Initially ruling as a ban, he ascended to the throne after consolidating control over the nobility and securing Bosnia’s independence from external influence. In 1377, he proclaimed himself King of Bosnia, marking the transformation of Bosnia from a banate into a kingdom.

Tvrtko I was an ambitious leader. His military campaigns expanded Bosnia’s control over key coastal cities in Dalmatia, enhancing its economic and strategic position. He also established a presence in Serbia after the fall of the Nemanjic dynasty, even claiming the Serbian throne. At its height, Tvrtko’s Bosnia was one of the most powerful states in the Balkans.

Trade flourished under his reign, particularly with Venice and Ragusa. The kingdom’s economy was bolstered by silver mining, which allowed Bosnia to mint its own currency. Tvrtko’s leadership brought stability and prosperity, earning him recognition as one of the most capable rulers in Bosnian history.

Religious Complexity and the Bosnian Church

One of the most defining aspects of medieval Bosnia was its religious landscape. The Bosnian Church, often labeled heretical by both the Catholic and Orthodox authorities, maintained a distinct doctrine and structure. It was neither fully aligned with Rome nor Constantinople, which made Bosnia a target for external religious intervention.

The arrival of the Franciscan Order in the 1340s, backed by the Hungarian crown, sought to reassert Catholic influence in Bosnia. This led to a prolonged struggle between Catholicism and the Bosnian Church, culminating in the gradual decline of the latter by the late 15th century.

The Decline and Fall of Medieval Bosnia (1391–1463)

Following Tvrtko I’s death in 1391, Bosnia faced increasing internal instability. His successors lacked his leadership strength, and noble factions vied for power, weakening the central government. At the same time, external threats grew, particularly from the Ottoman Empire, which had begun its conquests in the Balkans.

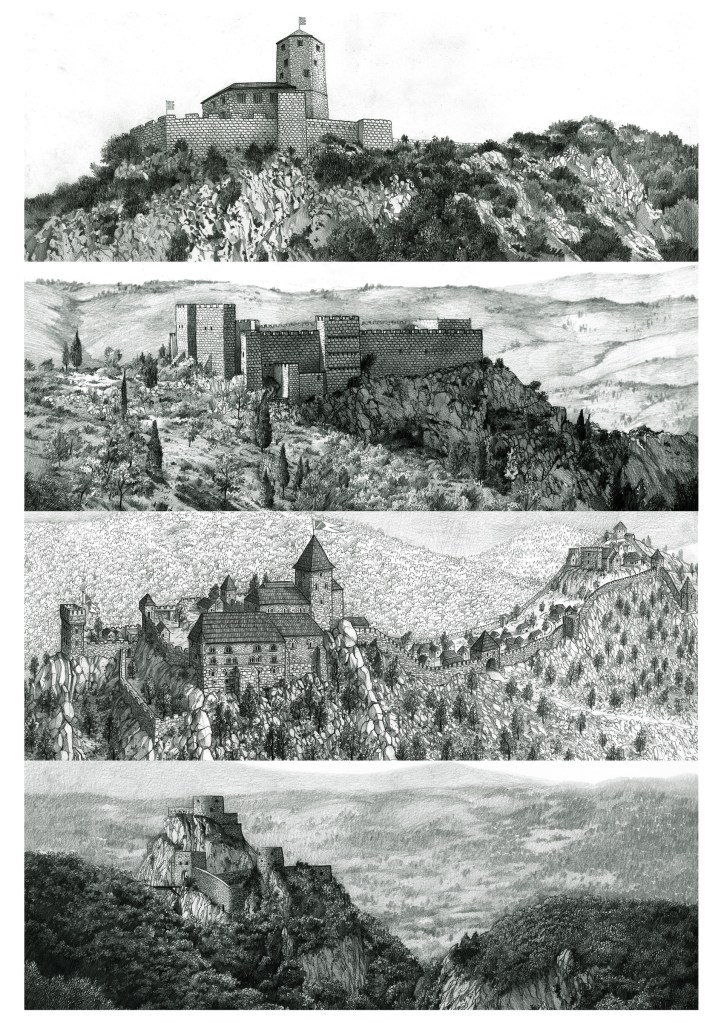

By the mid-15th century, Bosnia was caught between Hungary and the Ottomans. The Hungarian crown sought to maintain its influence, while the Ottomans steadily advanced into the region. The final blow came in 1463, when Sultan Mehmed II launched a full-scale invasion of Bosnia, capturing its last king, Stephen Tomasevic. The fall of the capital, Bobovac, marked the end of the medieval Bosnian kingdom.

Legacy of Medieval Bosnia

Despite its fall, medieval Bosnia left a lasting cultural and historical legacy. The unique stecci (medieval tombstones), scattered across Bosnia and Herzegovina, stand as monuments to the kingdom’s rich heritage. The Kotromanic dynasty’s achievements in governance, trade, and diplomacy set the foundation for Bosnia’s identity, even as it transitioned into Ottoman rule.

Today, the history of medieval Bosnia is gaining renewed interest among historians and scholars. The kingdom’s ability to maintain independence for nearly three centuries, despite external pressures, highlights its resilience and strategic importance in the medieval Balkans. The rise and fall of medieval Bosnia is not just a story of conquest but of cultural endurance and political intrigue, making it a fascinating chapter in European history.